My first years of public education, in the 1960s, were at all-white elementary schools in Florida. That’s despite the fact that in 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in schools was unconstitutional. Only when I was in fifth grade, after my family moved to Lawrence, Kansas, did I have Black classmates. I don’t remember it being a big deal. But for Black kids who were at the forefront of school desegregation, it not only was a big deal, it was often a terrible ordeal.

For background information on Brown v. Board of Education, Little Rock Central High School, and the two National Historic sites that tell their stories, see my article in 10Best.com/USAToday.

Adversity in the face of school desegregation

Take Ruby Bridges. She was only six years old when, on November 14, 1960, she became the first African American to integrate an all-white elementary school in New Orleans. For the entire school year, Ruby was taught in a classroom by herself, segregated from white students. She was also accompanied to school every day by federal marshals, to protect her from angry protesters.

Unfortunately, resistance to school desegregation played out all across the country in the 1950s and ’60s, mostly in the South. For Black parents who were among the first to enroll their children in all-white schools, they did so mostly to procure a better education for their kids. After all, it was painfully obvious that many Black schools were blatantly inferior to their white counterparts, hobbled by insufficient funding and occupying everything from converted church basements and vacant stores to even empty school buses.

But the decision to be among the first to integrate schools was hardly an easy one. Indeed, sometimes it was a dangerous one. Some African American parents lost their jobs for enrolling their kids in all-white schools. Threat of violence caused others to leave town. Countless more were so frightened of consequences, they chose to leave their children in inferior all-black schools.

In Virginia’s rural Prince Edward County, the only high school for African Americans lacked science labs or a gym; later “improvements” were the additions of a few unheated tar-papered shacks. In 1951, 16-year-old Barbara Johns organized a student walk-out with Black classmates to demand a new school, but in the end she was sent to live with relatives to escape the volatile situation. Indeed, Prince Edward County was so opposed to integration, it simply closed its schools from 1959 to 1964.

In Clinton, Tennessee, Jo Ann Allen Boyce was one of 12 Black students to integrate the town’s high school in 1956. After only four months, however, her family moved to California to escape the hatred that rocked the town, fueled in part by outside agitators. A white pastor who had escorted Black students to school was beaten. Later, 100 sticks of dynamite damaged the school.

When African American students attempted to integrate a school in Tchula, Mississippi, the school was burned down–twice.

Little Rock Central High School

Probably no school drew more international attention on the rocky road to school desegregation than Little Rock Central High School. In 1957, on orders from the governor, the Arkansas National Guard blocked a group of Black students now known as the Little Rock Nine from entering the school. One of the Little Rock Nine, Elizabeth Eckford, found herself surrounded by an angry white mob, which yelled racial slurs and spit on her repeatedly, even as she waited 40 minutes for a bus to carry her to safety.

Only weeks later, after riots by angry white protesters were broadcast on TVs across the country and President Dwight Eisenhower called in 1,200 soldiers and federalized the Arkansas National Guard, were the Little Rock Nine allowed in to school. Yet even though federal troops remained at Central High the rest of the year, the Little Rock Nine endured documented physical and verbal abuse, including constant name-calling, kicking, tripping and urine and feces dumped in their lockers. White students who talked to the Nine were also threatened. After the school year ended, Little Rock closed its public high schools for a year rather than integrate. It’s known as the Lost Year.

This doll, on display at the Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Site in Topeka, Kansas, is one of four dolls used by social psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark to study the effects of segregation on school children. When African American children were presented one black doll and one white doll and asked which one was “nice,” which one they most preferred to play with, and which one most looked like them, they mostly chose the white doll. The Clarks concluded that segregation gave African American children a sense of inferiority that could last the rest of their lives. The results were key in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which ruled that “separate education facilities are inherently unequal.”

Adults made school desegregation worse

Based on what I’ve read, it seems that most of the resistance and hatred directed at school desegregation was fueled by adults. School administrators banned Black students from school activities like basketball and proms and blamed Blacks for altercations. White community members protested, made threats, or worse. White students who might have made overtures to their African American classmates were often strongly dissuaded from doing so, either through threats or bullying.

In fact, some Black students who were at the forefront of school desegregation maintain that if the kids had been left alone, things might have turned out differently.

That’s the opinion of Minniejean Brown, one of the Little Rock Nine, who was expelled after altercations at Central High.

“You know what? If there hadn’t been opposition, we wouldn’t be here,” Brown said at a press conference I attended last September in Little Rock to commemorate 65 years since integration. “We would have melted into that school of two-thousand white kids and nine Black kids and there would be nothing historic about it. So the story exists not because we wanted to go to that school, but because of the opposition to our going to that school.”

I think about that today when I read about parental and political opposition to transgender-affirming policies, books in libraries and the teaching of systemic racism–or even slavery–in our schools.

The battle for equality is clearly ongoing.

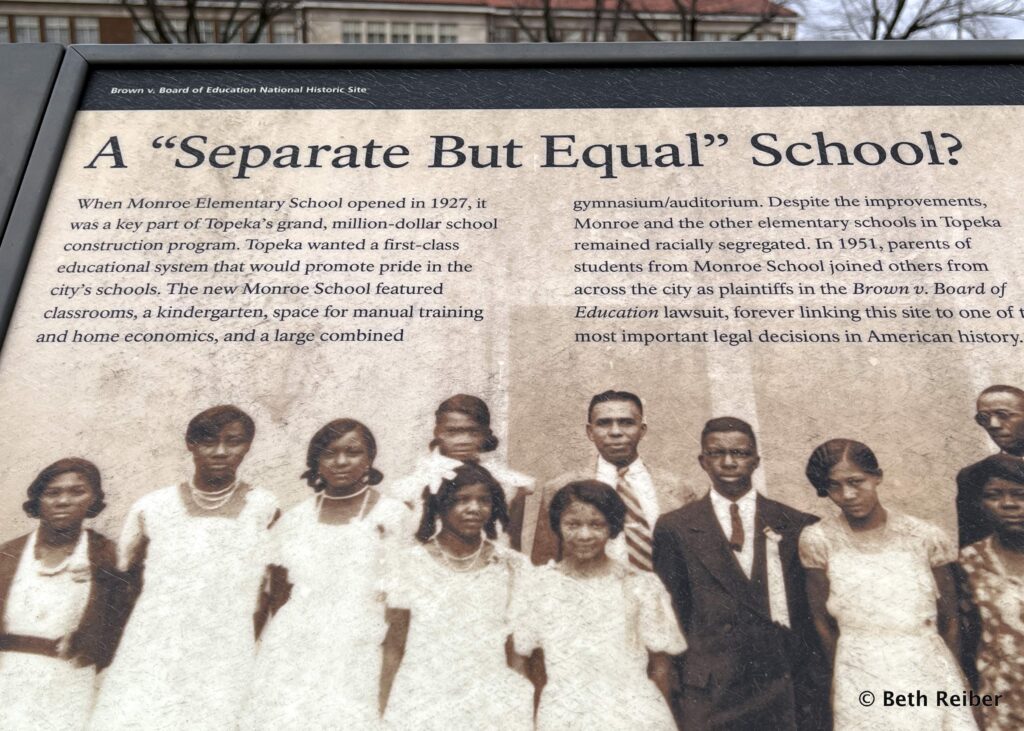

Two schools at the forefront of desegregation are now part of the National Park system: Little Rock Central High School and Monroe Elementary in Topeka. For more about visiting both sites, their history and their importance to the Civil Rights movement, see my article in 10Best.com.

Other articles I’ve written related to Black history include Greenwood Rising: Tulsa’s Black Wall St. Memorial, about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and Learning about Slavery in Charleston.