I didn’t appreciate what I was seeing as I walked the stone streets of Ostia, ancient Rome’s port city, gazing at what used to be taverns, inns, baths, bakeries, temples, markets, warehouses, and apartments. It was only later, after visiting Italy’s hugely popular Roman Empire attractions like Pompeii and the Colosseum, that I realized how far off the radar Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica falls.

It doesn’t have the crowds. It’s a great introduction to ancient Roman lifestyles. It shows how they lived, where they worked, where they ate and the answer to that most vexing question of all–where they relieved themselves. While Ostia does not have Pompeii’s wealth of excavated buildings and painted frescoes, or its pull of walking through a 2,000-year-old brothel, Ostia is only a 45-minute commute from Rome, compared to the more than three hours it takes to reach Pompeii. If your time is limited, therefore, this is a great alternative. Plan on spending the better part of the day at Ostia Antica.

While Pompeii gets all the glory, consider visiting Herculaneum instead if you have time. Also buried by Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE, it’s better preserved and draws far fewer crowds.

The rise and fall of Ostia, ancient Rome’s port city

The Roman Empire was vast, stretching from the Atlantic across most of western Europe through northern Africa. A fifth of the world’s population lived within its reach. Rome, of course, was the center of it all, home to as many as a million people. But how to get the riches of a huge empire to the people of Rome?

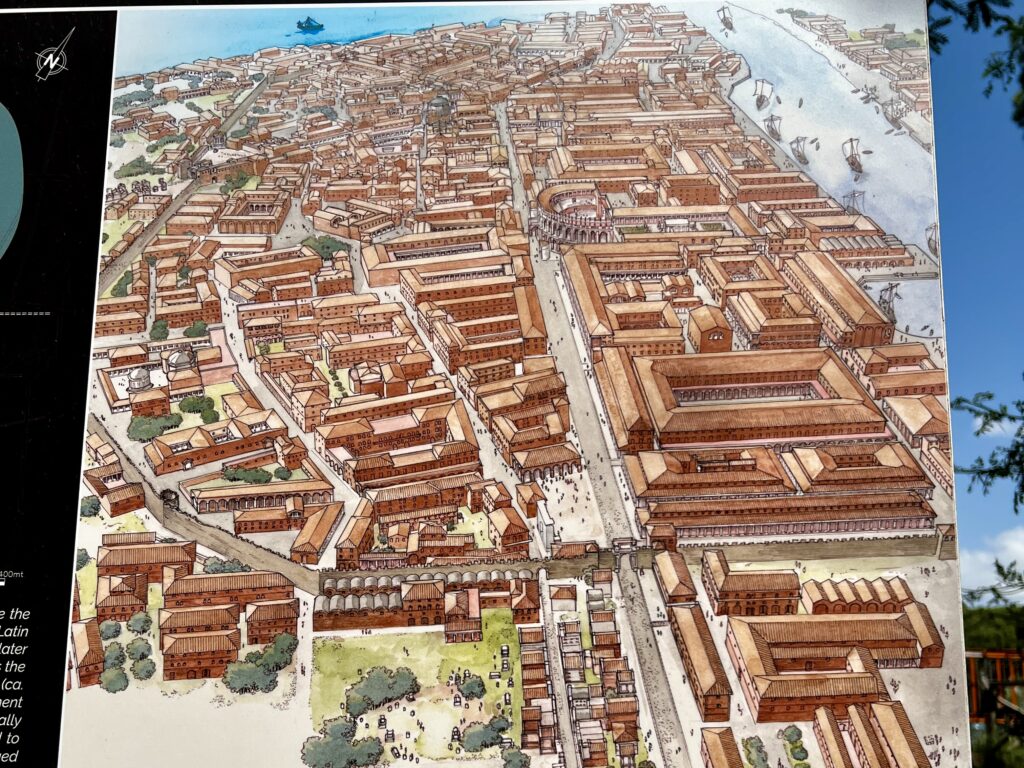

Enter Ostia, which served as ancient Rome’s port city at the mouth of the river Tiber (its name stems from the Latin ostium, meaning “river mouth”). Ostia’s heyday matches that of the Roman Empire, primarily from the first through third centuries CE. With the collapse of the empire, Ostia’s raison d’etre dissolved, sending it into a gradual decline exacerbated by tsunamis and earthquakes. Over time, Ostia became covered in silt and sand, which helped to preserve it.

Excavations over the past century have uncovered only a third of the once-thriving port. Most of the buildings, which today are protected as the Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica, date from the first three-quarters of the second century. They are mostly brick, even though ancient Romans covered brick with plaster or marble. But marble proved irresistible and was carted off long ago for use elsewhere, including cathedrals in Pisa, Florence, and Amalfi.

The people of Ostia

Because of its role as a seaport, Ostia was a densely populated international city of about 40,000 people. It bustled with activity common to ports everywhere, with imports off-loaded from ships anchored at harbor and brought to warehouses. Tow-boats, pulled by slaves or oxen, then transported goods on the Tiber more than 20 miles to Rome.

It’s hard to imagine how Ostia might have looked like back then, but surely it was crowded and noisy, teeming with merchants, sailors, dockworkers, porters, and owners of shipping companies, as well as the townspeople and slaves who catered to them with taverns, inns, public baths, and markets. Because of its importance to Rome, Ostia even had a brigade of about 300 firemen.

But most fascinating to me is that immigrants and freedmen (former slaves who were freed) were drawn to Ostia from all walks of life from all over the empire, including Spain, Greece, Turkey, Syria, and North Africa, giving it an exotic atmosphere few Italian towns could match. Needless to say, it’s the kind of place I would have liked to visit and write about.

I guess I did, only 2,000 years too late. Luckily, Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica was holding living history demonstrations the day I was there, with people dressed in period costumes performing as dancers, musicians, basket weavers, cobblers, bakers, slaves being herded to market and other activities. It brought the town to life.

Visiting Ostia today

Today, visiting Ostia, ancient Rome’s port city, is akin to strolling around an open-air architectural museum. Shaded by umbrella pines and cypress trees, with poppies and other wildflowers providing pops of color and mourning doves sounding their haunting coos, Ostia offers 370 acres of easy exploration. The joy comes from aimless wandering, a happy escape from Rome’s crowds.

Upon entering Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica, you’ll find yourself on the wide thoroughfare that connected ancient Ostia with Rome, some of the stones still showing the ruts of countless chariots that passed through.

Civic life in Ostia, ancient Rome’s port city

Ostia’s forum, the administrative center of every Roman town, is just a shadow of its former self, with the Capitolium, a temple dedicated to gods Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, the only surviving building.

More rewarding is Ostia’s theater, one of the oldest masonry theaters in the world. Of course it has perfect acoustics. Beyond is Ostia’s commercial center, a grand, open piazza variously known as the Square of the Guilds or the Square of the Corporations. This, to me, is Ostia’s highlight. With a temple now at its grassy center, the square was once lined with the headquarters of more than 60 companies, where ship owners, shipbuilders, traders, merchants, and entrepreneurs from Ostia and all around the Mediterranean met their clients and prospective customers.

This is where it all happened, where bargains were struck and deals were made for imports pouring in from around the Roman Empire, including grain from Tunisia and Egypt and marble from Greece and Turkey. Even exotic animals passed through on their way to the Colosseum (I later learned on a tour of the Colosseum that 9,000 beasts were killed in the arena’s first 100 days; a half-million were slaughtered overall).

I loved walking around the square, because in front of each former company is a mosaic advertising their business. Amphorae, for example, suggests the importation of wine, while an elephant might mean a trader from Africa.

Private life

But I’m also always interested in how people lived and where they ate. There were many multi-level apartment buildings (insulas), with most people living in rented flats. The House of Diana is a multi-level apartment with a tavern on the ground floor, where the shopkeeper lived one floor above and middle- or lower-class occupying the top floors. While the wealthy had kitchens and latrines of their own, renters on top floors had no running water or cooking facilities, making their abode clearly just a place to sleep.

Never mind. Romans enjoyed dining out, and there were plenty of taverns for a cheap meal, with still-life wall paintings acting as menus and shelves laid out with offerings of olives, eggs, lentils, meat, fish, and other popular fare.

Bathhouses, too, were very much a part of Roman life. Ostia’s Forum Baths was one of the largest, with four changing rooms, a cold bath (frigidarium), a room for sunbathing, a room for sweating, a lukewarm room with a heated floor (tepidarium), and a hot bath (caldarium).

But it’s the public latrine that sends shivers up my spine. Accessed through a revolving door, the latrine consisted of a marble slab running along three walls, with 20 holes serving as toilets and no partitions between them. Human deposits went straight down the hole to a channel with running water to flush it all away. In the floor in front of the seats was another channel, this one with clean water, useful for dipping the communal sponge attached to a stick for cleaning.

Those ancient Romans were brilliant, inventing concrete and the water wheel, laying 50,000 miles of hard-surface roads throughout their empire, and perfecting arches, aqueducts and sewer systems. But toilet paper? Apparently, ancient Romans didn’t see the need.

For more on ancient Roman life, see my article Herculaneum Then and Now. For more on Italy, see my articles Limoncello 101: Where to try it and how to make it and Venice the Improbable City.

My other articles on Italy include